We’ve talked about general experiences, we’ve talked about music, a bit about liturgy..now let’s talk about penance.

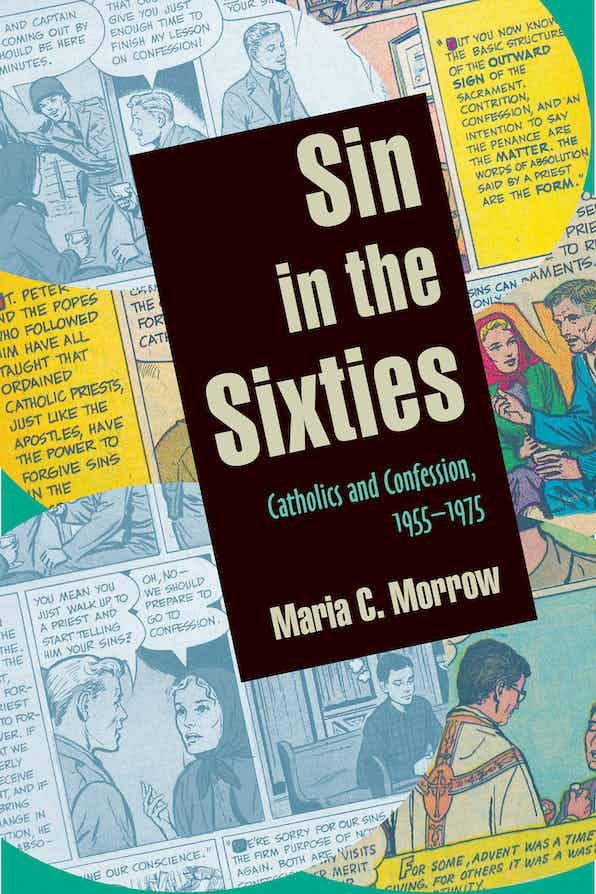

I’m going to share some interesting thoughts from Sin in the Sixties by Maria C. Morrow, then relate a bit of my experiences of the era (spoiler alert: not much, to tell the truth), and then invite you to share your own experiences. Remember this is not intended to be a debate or discussion spot. I’d just like to hear what your experiences were, both before and after the Second Vatican Council, although since I’m sharing the insights from a particular book, you might feel moved to comment on that – so feel free - and again, from any perspective, of course.

I have to say, too, that while I initially pitched this as being mostly about Confession, this post is going to focus on more general penitential matters - but you can take on any of it.

Sin in the Sixties is a good account of the changes in thinking and practice related to penance among American Catholics. The unique contribution of this book is the way in which Morrow contextualizes the changes in the form and practice of Confession within the general framework of penitential devotional practices.

I won’t summarize the book – you can find the table of contents and some excerpts here – but I’ll just share with you some of the most important and (to me) interesting points.

First, a couple of document links:

Paenitenmini - Paul VI’s 1966 Apostolic Constitution on fasting and abstinence.

The United States bishops’ 1966 document on penance and fasting.

Not a document, but 1976 NYTimes article on the revised rite of Penance.

What Morrow emphasizes is something I’ve discussed on my other blog a few times, including here. There were a number of theological and philosophical shifts that occurred during this period, but in terms of penitential practices, the most important was the change in emphasis from obedience to freedom.

The argument was that pre-modern Catholics were formed in a framework of obedience to authority as the model of holiness. It was time for a change, it was argued, not only because modern man was more oriented towards democracy and freedom, but because the obedience model truly was detrimental to human flourishing.

The most prominent voice on this score, particularly in relationship to morality, was Bernard Haring. Some quotes from Morrow:

One of the criticisms that moral theologians like Bernard Häring had about manual-based moral theology was that it tended to foster a minimalistic morality. The faithful tended to do the bare minimum to fulfill what they saw as their Christian duty and confess what was clearly delineated as a transgression of law. The focus on obligatory practices such as Friday meat abstinence and attendance at Sunday Mass, as well as a preoccupation with sexual sins detracted from a holistic sense of charity that would foster awareness of a more diverse number of sins. including social sins such as racism or buying grapes that were harvested by un-justly paid farm workers. The manual-based morality of the confessional was regarded as minimalistic in the sense that the faithful did not strive to advance beyond what was required of them by the church. It was narrow because it often failed to consider the bigger picture—the many sins that were not detailed in the manuals but could be just as important.

Häring saw his work as moving beyond this minimalistic and narrow morality rooted in the confessional. Häring and those influenced by his work saw themselves as calling the faithful beyond the bare minimum required by the law to something greater—"the law of love—that truly would lead to sanctity rather than scrupulosity mused by legalism. (237)

And:

Häring was confident that the truly mature Christian with a strong interior life would not simply choose the easiest route in a particular situation, but would make the more valiant decision. Hence the free will acting on the law of love would naturaly go above and beyond the obligations imposed by an external authority. In contrast to this was the faithful’s preoccupation with following a multiplicity of laws and obligations imposed on them by the church, which Häring believed often distracted the faithful from acting out of love. (101)

And:

This was, indeed, the dominant model from the Council on, and perhaps it will help explain why, when you listen to figures like Pope Francis, you hear a consistent implication that church structures of any kind are generally not doorways and guides to a fruitful relationship with God, but rather obstacles.

Rather than seeing obedience to the church’s rules as an external manifestation of the interior disposition, many Catholic theologians tended to view obedience to these laws as preventing the proper interior disposition by causing undue concern with the law. (80)

Of course, this is a genuine tension in Christian life. Read Galatians lately? And of course, Martin Luther picked up one strand of that rope and yanked it hard – see On the Freedom of a Christian.

Morrow highlights the two major voices of the period articulating a different view - Jesuits John C. Ford and Gerald Kelly:

The dissatisfaction with obligationalism could become dissatisfaction with obligation; irritation with legalism could become irritation with law; and fondness for the concrete, personally creative, and subjectively satisfying could tend toward a belittling of the abstract universal and objective values of morality applied to specific cases. In particular, it seemed to them that critics of obligationalism contended that sanctity only began where obligation ends….(88)

I keep telling you, here and at the other place, that these arguments are not brand new…..

The second aspect of this I want to pull from Morrow’s book is the more practical, pastoral implications of the changing theological winds.

Yes, as she points out, the changes in penitential practice (fasting and abstinence) and the sacrament of Confession, had some motivation in the desire to fit into 20th century western culture. But at the root of it – as clearly articulated in the documents – was the belief that the manualist-legalist-obedience framework led to spiritual immaturity and minimalistic belief and practice, enabling Catholics to focus on matters that might not be that serious and ignore the call to mature spiritual growth and social sins like racism and social inequality.

Tied to this as well, were the reforms of the liturgy. It’s important to understand the big picture here. One stream of post-Conciliar activity emphasized the new Mass – simplified, in the vernacular, more accessible – as the solution to a lot of perceived problems.

The reason all of these (it was believed) crazy, non-Biblical, sometimes superstitious devotional practices, including penitential ones – had developed, spun out and held so much interest with Catholics was that they could not understand what was going on in Mass (it was said) and were disengaged from the power of the Eucharist. If they could develop a closer relationship to Christ through the Mass, the source and summit of the faith – then they wouldn’t need all that other stuff. They would, for example, have a greater engagement with God’s mercy through an understandable penitential rite and more frequent reception of the Sacrament.

(Which is why, post Vatican II, in many parts of the Catholic world, all these devotions dropped away and were even forbidden. Everything was supposed to be found in the Mass.)

What I particularly like about Morrow’s take is her gently-worded, yet pointed conclusions about church leaders “confidence” in both the impact of these changes and the desire of Catholics to be free of obligation and choose-their-own penitential practice. To get a sense of this, read the 1966 document.

The specifics? All of the previous fasting and abstaining was abolished as obligatory except for Fridays during Lent and Ash Wednesday. Previously, of course abstaining from meat had been obligatory on every Friday. Every day of Lent had been a fasting day (one regular meal, two collations, only one of the meals could contain meat). Ember Days and Vigils to certain feasts had also been days of fasting.

Fridays were still treated as a day of penitential practice, but as the document exhorts, individual Catholics were now free to fashion their own penance, in tune with their own individual spiritual growth.

(Note - as Morrow does - that the fasting and abstinence rules have been in continual flux throughout church history, and even in the United States, various indults and dispensations had been sought since the Church was formally organized in the US.)

As she points out, the pre-Conciliar landscape was a closely-woven fabric of social structures and church practices. Forces outside the church were, of course, dismantling the former. Morrow articulates the problem very well. Some quotes:

The move from socially instituted, communally practiced penance to individual chosen penances was a response to recognizable problems in penitential practice; nonetheless, the attempt at reform ultimately destabilized the established structures of penance without replacing them with social structures that would better facilitate nonsacramental penitential practice. (161)

It is evident that the bishops wrote from a standpoint of great confidence in their congregations’ penitential ability and commitment to penance.

The bishops seemed to express confidence in their congregations’ commitment to Friday penance in their decision to introduce an element of choice to the Friday sacrifice. This new and diversifed penance would become a point of renewal for the church as the faithful became more individual proactive in regard to their penance. The bishops apparently believed that Catholic would understand that Friday penance had not been dropped but rather modified. (179)

And:

But selecting and remaining committed to a person’s own unique penance without adequate social support can be quite difficult. Though the theory behind it indicates an important point as to the significance of the interior life of the person, in practical terms it is difficult to assure that individual penance happens. Without law there is encouragement and exhortation, and this can be effective as motivation. However, in this particular context of great demographic change for Catholics and major ecclesiastical change regarding the celebration of the Mass, penance was likely unappealing, seen more as a throwback to before Vatican II in the Catholic ghetto than as a crucial part of the future of Catholicism in the United States.

The move to make penance depend upon the choice of the individual diminished the context of community solidarity and support, hence relying upon a person’s intention and willpower to execute on the intention of making satisfaction for sin. Furthermore, the reduction of penitential days lessened the habitual nature of fast and abstinence….

…Despite the problematic legalistic tendency of obligations, the penitential regulations had provided an impetus that both reminded the faithful of the need to do penance and provided them with a community in which to do that penance. (189)

I must say, the incoherence is striking. So, the older penitential practices were deficient and led to superficiality, minimalism and hampered spiritual growth. Now, the people so poorly formed by those practices that you think were terrible are going to jump at the opportunity for freely-chosen intentional penance? And that will work how?

So…my experiences? Barely remembered, so sorry about that.

I have no recollection of my First Confession or any confession before high school. Did I go? Was I taken? Probably, but not very often, despite my mother’s faithfulness (complicated, but real). My only useful memory for this matter is related to the changes in 1976 – the change in the rite itself

and then the change to face-to-face confession.

Filmstrips. During Mass. That’s what I remember. Three Sundays in row at the parish, being shown filmstrips about the new rite. … I think that might have been one of the things that finally drove my mother to stay home on Sundays, leaving me to drive to Mass by myself…..

So what about you?

My first confession was in about 1974. I stopped going for about 15 years when my sins started to get a bit "juicy". I'm 57 now. I still feel the need to confess some of my teenage sins, when the memories come to me. I just recently confessed stealing 8 cases of Heineken from a delivery truck, with 2 of my friends, when I was a kid. The priest was great. I said something like "Father, my friends and I did so many dumb, sinful, things and I just remembered this one I never confessed". He said "that happens to me all the time, lay it on me". He also talked about this confession as an encounter with Jesus. He was very talkative, and the penitents were stacking up outside the confessional.

I've had nothing but good experiences in confession, and try as I might, I only got my wife to go once as an adult. She brings her mother monthly and I try to encourage her gently about once a year.....we can't crack her!

I tell my friends and family that if they are frightened, and haven't been to the sacrament in a long time, to go to confession in NYC, to St Francis of Assisi church on 33rd st......right across from Penn Station. They've heard it all a thousand times. Good luck trying to shock those priests! I would put it in second place behind places like Fatima and Lourdes for the amount of confessions heard.

I feel like a lot of the emphasis on obedience might’ve been better served by a focus on humility. Penitential attitude flows from humility more than a more detached sense of obedience, not that they aren’t connected.

And, from the clerical perspective, greater humility might’ve saved us from the liturgical abuses and irreverent masses post-1969.