Yes, this is a reprint..of a reprint. I published the original post in 2008, which is unbelievable to me, really. But since one of the reasons for this space is to collect what I’ve previously written on the Second Vatican Council, here you go.

No comments on this one, but next week, please come back for a comment-open post on religious education in that era - building on Jesus Livingston Seagull.

But this blog post, which was an excursion through a book originally published in 1960, points to what was going on in the liturgical movement in the West well before Vatican II. I don’t present all these years later it in order to blow anyone’s mind – hopefully everyone knows this – but to bring out some interesting factoids to the present discussion.

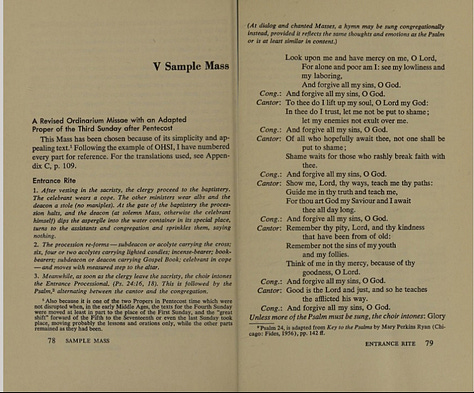

Published in 1960, written by the well-known figure in the U.S. Liturgical Movement, Fr. Hans Reinhold, the book is a slim (very slim) summary of where the liturgical movement stood at that point.

(I’m thinking I don’t have to do Liturgical Movement 101 for this crowd – not that I actually could, if pressed, but you probably know that modern, intentional liturgical “reform” didn’t begin with the end of the Second Vatican Council. For almost two hundred years, scholars and others had been thinking through liturgical issues, beginning with music in the early 19th century, with work done on Gregorian Chant. Fueled by the 19th century interest in history, in ancient origins of religious beliefs and practices, early documents such as sacramentaries and so on were the subject of new research. In the early 20th century, the Popes took an interest in liturgical spirituality, particularly Pius X and then, moving on, Pius XII, whose Mediator Dei functioned as a foundation of the thinking and work that accelerated after World War II and then who promulgated the 1958 Holy Week reforms.)

The goal was, in essence, bringing out the reality at the heart of the Mass so that the laity might spiritually benefit and that their relationship with Christ through the Eucharist might be nourished more directly and powerfully.

I think that probably is a decent, if basic summary of the basic intentions of the liturgical movement. Many other ideas and purposes flow from that. But I do think that the great concern (very evident if you read Mediator Dei) was that the laity come to understand and experience Christ in the Eucharist as the center of their spirituality.

The thinking was that the shape of the Mass and the way it was celebrated and experienced in the 20th century obscured this.

To understand this a little better, know the other dimension of the “liturgical movement” in the 20th century, other than what scholars and monasteries and some dioceses were doing in terms of reforming the Mass (using the vernacular and so on) was the move to bring laity to the Eucharist more knowledgeably and consciously.

So, for example, there were movements during the 20th century, before Vatican II, to increase the number of people receiving Communion – not by simply telling them to get up there and go, but by encouraging more frequent Confession. There was a great emphasis on helping the laity understand what was going on in Mass and connect with it directly. Missals – now allowed to offer vernacular translations of texts – were very detailed. Many books and booklets with this aim were published. Catechetical materials for children and young people devoted a great deal of space to this purpose. Everyone from Ronald Knox to Romano Gauardini to Fulton Sheen was on the case. Oh, and Pius XII, too, in case you’ve forgotten.

So you’ve got two factors working here – connect the laity more consciously to Christ in the Eucharist – and take a look at the structure of the Mass from various perspectives.

Notice the absence of Freemasons.

I’m not saying that there weren’t people involved in the Liturgical Movement who had less than lofty motivations, skewed theologies, or who were working from very flawed assumptions (and incomplete, biased historical knowledge), but I think before you can discuss the liturgical movement, you really have to try to see it, as best we can, through their eyes.

There was, indeed, a great deal missing from the equations they were constructing, which became abundantly clear later. From the perspective of the present, we can look at some of what was proposed (and done) and say, “What were they thinking? ” But we’re saying that from our perspective of a half-century or more down the road, and it’s never fair to expect historical actors to have 20/20 hindsight.

Which actually, and finally, brings me to the book. It’s a really interesting little book, and available – there are used copies available here and there and you can borrow it for an hour at a time here.

In it, Reinhold gives a little background, then goes through the Mass and summarizes the major changes that were envisioned by the majority of scholars by 1960. His primary points of reference, aside from the scholarship of the time, were various 20th century papal encyclicals as well as the 1958 reforms of the Holy Week liturgies. He does not take much time to discuss language because he assumes, I think, that replacing Latin with the vernacular most of the time was definitely on the way.

…as were the rest of the reforms. A blurb on the back from Jungmann says, “The book, concise and to the point, may be helpful in the task of preparing the Christian people for the reforms to come.”

What would this Mass look like? Essentially what we have now with a few particular exceptions and some general assumptions that definitely did not carry over, and did not even seem to last a decade.

Entrance Rite: (Which is what he calls it – most the “parts” of the Mass, in his schema, have the names by which we call them today). Essentially the same except for Asperges and no Confiteor. The celebrant wears a cope, the other ministers, albs.

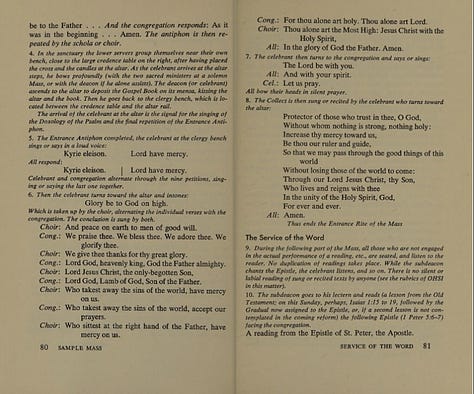

“Service of the Word” – Old Testament, Gradual, Epistle, Alleluia, Gospel, homily, “bidding prayers” Confiteor follows Bidding Prayers. By the way, the form of the Bidding Prayers offered by Reinhold is very Eastern in feel, which is interesting.

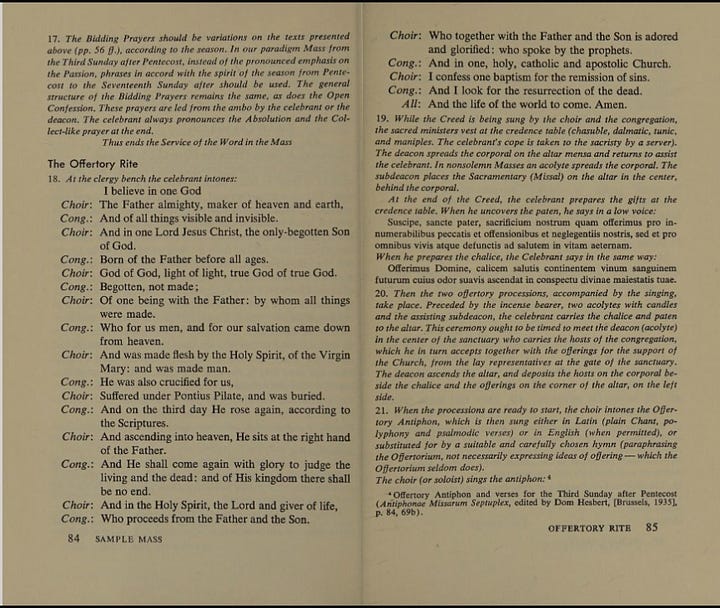

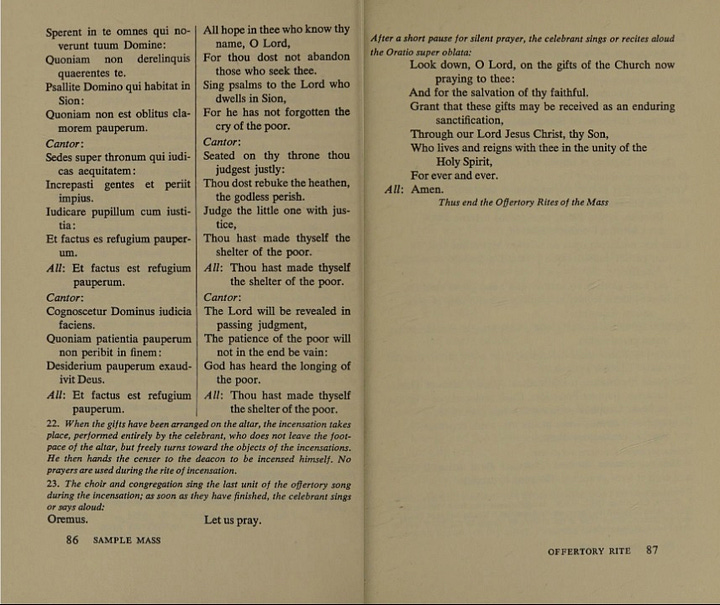

Offertory Rite: Credo. While Credo is being sung, altar prepared, ministers vest. Very stripped down offertory (this was one of the main objects of reform – the offertory, which was felt to be overextended). Silent prayers by celebrant, Offertory antiphon (or “other suitable song”)

Canon: Reformed Canon, audible, chanted, but only one. No other Eucharistic Prayers envisioned (at least here). Congregation stand except during Consecration.

Communion Rite: Lord’s Prayer, Kiss of Peace – using Pax tablets. Agnus Dei. Pretty extensive prepatory prayers from celebrant. Distribution of Communion (altar rail is mentioned). Various prayers. Dismissal.

Several points about this and the broader vision were quite interesting to me:

1) The various classifications of Masses remain – Solemn, Chanted, Low (of which there are two types – Recited, with vocal congregational participation, and Recited with no congregational participation.). Reinhold struggles with what to call Private Masses – he clearly sees the end of them in sight, but determines that as as long as they remain they might be called “devotional Masses.”

2) Reinhold, at least, does not state any sense of elimination of subclerical states with their specific roles in the Mass. He also holds up the continued role of the choir. In fact, he sees the quality of music during Mass as very important and sees congregational participation in music a good, but risky thing. For example, in speaking of the Gradual, Alleluia, Tract and Sequences, he writes:

They are elaborate compositions, both in their chant settings and in polyphony, and cannot, therefore, be sung congregationally. I think this is all to the good: a reflective mood should now settle over the congreation as being now an audience, definitely receptive during the Service of the Word. Here they should be given a “break” in constant response and activity (quite apart from the fact that some phase of the service should be allotted to good music as such.)

Where a good schola is not available and the danger of mediocre or poor music exists, there is still the possibility of using a soloist, or psalmodic singing or recitation by a chorus, or of a choral hymn, which of course should conform to the minimal requirements for such hymns as expressed in the Instruction: It should be good musically; in content it should express teh thoughts and moods of the displaced texts; and it should be in the spirit of the season if not of the very texts which are read on this occasion. (54)

I am not familiar with what was going on in the world of sacred music at the time, but from reading this, as well as other texts from the period, it seems to me that aside from the allowance of “other suitable songs,” these chants and other traditional musical elements of the Mass were envisioned to remain in a form largely in continuity with the past, perhaps in translation – but even that is not assumed.

3) Reinhold speaks strongly against “unauthorized experimentation” with the liturgy and seems to assume, based on the experience with the Holy Week Rites and what was happening in the Curia, that liturgical reform, when it came, was going to come from Rome (which it did, of course, but with many, many actors and forces involved).

4) Reinhold’s summary of the purposes of a reform are not news to anyone familiar with the movement, but bear repeating in his own words:

“The clearer the essential outline of the Mass becomes, the better.”

“Since parish liturgy is for the parishioners, it should be made as lucid and simple as possible without oversimplifying its nature as a mystery…or losing its dignity, and its beauty”…

“Empty and now meaningless rites, excessive allegorism, wordiness and foreign elements should be eliminated…”

“The structural lines and the main points of emphasis should be unmistakable…”

“A maximum of participation should be made possible with a proper division of functions: the laity are no longer silent spectators, nor do they take over the role of any of the sacred ministers…”

“…freeing the core of sacramental worship from all unnecessary pomp…”

5) But…note this prophetic passage:

There is serious danger of overshooting the aim, once one embarks on the exhilerating task of putting things in order. Room must be left for “solemnity,” to avoid triteness, a romantically conceived “evangelical simplicity,” formless individualism, or the victimizing of the congregation by a tasteless and uninspired mystagogue. All that is noble and dignified, all that rises above ephemeral inspiration, must be preserved. The Roman liturgy is magnanimous, solemn, sober and warm: it should never lose these qualities, even when carried out in the smallest chapel. (37)

Sigh.

The book ultimately left me with a feeling of “What were they thinking?” Easy for me to say, again, with the convenience of hindsight.

I mean…think of it this way. How could anyone think that taking an ancient form of the Mass and totally reforming it in a matter of less than a decade would not turn out to be problematic? Reinhold refers to it as a “thorough reconstruction.” How could they not see that taking what Catholics had been taught was the “Mass of the Ages” and that in some way represented truths about their faith, not just in the content, but in the fact of its antiquity and universality and what those qualities expressed about the antiquity, solidity and universality of the faith itself…and then saying, “Oh, here’s a new one..” – how could they not see that as disruptive and a recipe for confusion?

It wasn’t, I know, a totally academic exercise. There had been experiments with reform and revision in various places, and perhaps the popularity of, for example, the Dialogue Mass, made people think that this would work just as they had envisioned.

I don’t know.

As I said – there are many points of this program I understand, intellectually, even as I disagree with some points of it. And there was, indeed, as I attempted to point out at the beginning of this post, a sense of liturgical reform in the air, even among the laity.

But what I just can’t grasp is the blindness in three areas:

Pastoral blindness as to how a wholesale, complete and relatively fast-paced reform would impact people’s sense of the Church, how it might even cause them pain.

Spiritual blindness that can’t see that there is a lot more to spiritual life and health that rational schemas, and that sometimes “lucidity” works to obscure, rather than reveal.

Blindness to human weakness, limitations and propensity to sin and self-centeredness, to twist the spiritual and people’s spiritual needs to serve the interests of those in power.