Yes, this belongs here!

This is a quick post before I head across the ocean for a week or so.

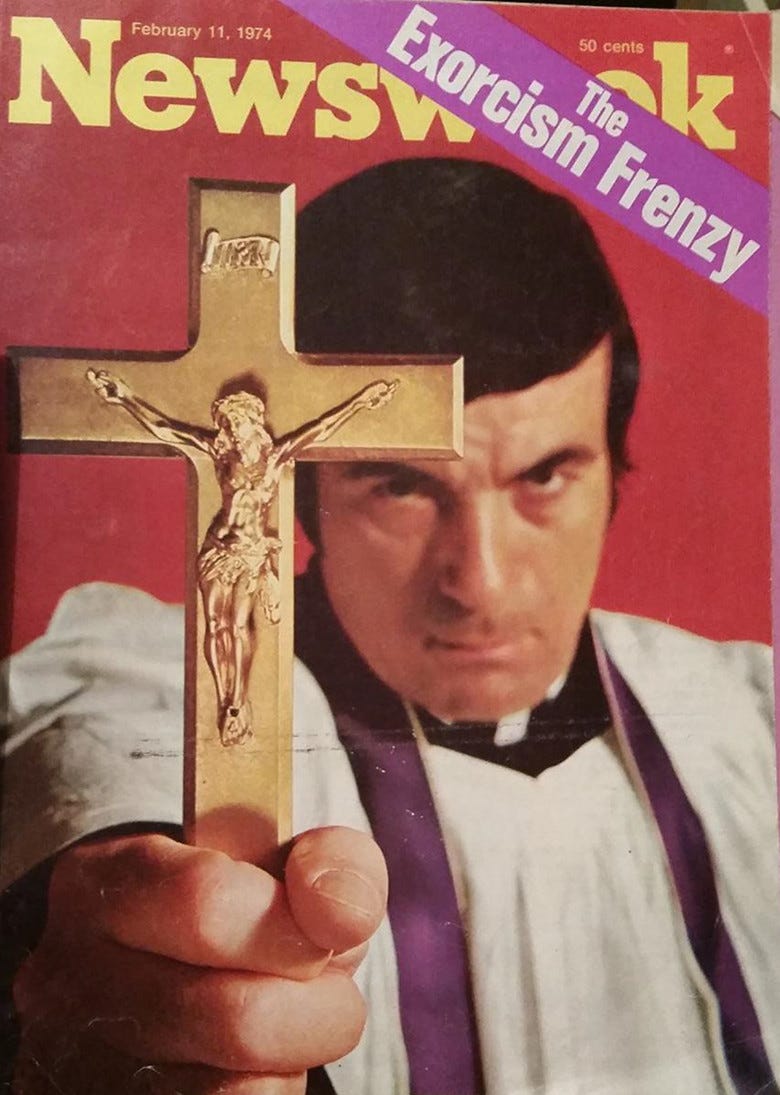

Last week, Chris Barnett and I recorded and released an episode of our series looking at our “Top Twenty Most Spiritually Significant Films.” It just so happened that my #18, perfectly timed for Halloween, was The Exorcist.

You can hear what I have to say on the podcast - Spotify, Apple all linked through the podcast’s show notes here - but I wanted to expand a bit and offer some links, since it’s related to the theme of this Substack: those immediately post-Vatican II years.

I have tried to maintain this space as one for sharing stories, not discussing, but this post is obviously an exception. Discuss away!

The Exorcist was released on December 26, 1973, and was a massive hit - not surprising considering its creative pedigree: William Friedkin directing and the screenplay by William Peter Blatty whose source novel was a bestseller for year. So of course, people were going to be interested.

I was in 8th grade at the time - public junior high in Knoxville, Tennessee. As I mentioned on the podcast, well - if your parents let you see The Exorcist - you were definitely living on the cool side of the tracks. I, of course, was not - nor did I want to see it.

(A couple of years earlier, the forbidden-movie-the-cool-kids-somehow-saw was Love Story - super scandalous because of the pre-marital sex, not, unfortunately for the hideous theme song and the lame and totally wrong tagline: Love means never having to say you’re sorry. What?)

But yes, it was a hit.

What I want to share with you in this space, is a bit about the contemporary Catholic reaction to the film. And that’s the primary reason I put it on the list - the movie itself presents an interesting spiritual landscape, particularly in relation to the struggles of Father Damian Karras and the questions around the final confrontation - but for my purposes, I think it’s significant mostly because of the Catholic elements it introduced into popular culture of the time as well as the reaction to it among Catholic commenters.

First of all, in a general sense, all of the Catholic accoutrements surrounding possession and exorcism were not a dominant aspect of popular culture before The Exorcist. You had crosses, holy water and vampires, but that’s really it. Catholic symbols and practices were not part of the horror landscape. I suspect that through most of the 20th century, there was a sense of respect for religious ritual in general that worked against it being used in this way, especially on film.

But then along came The Exorcist, and we are off to the races. From that point on, the power of Christ compels you, holy water, chant, priests in cassocks, crucifixes and yes, even Latin became common, easily understood tropes…

….just as they were being abandoned by Catholics themselves.

This, of course, did not please Catholics eager to move on and beyond all of that medievalism.

First:

The official Catholic response to The Exorcist, however, was not as reactionary as the press claimed. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Office of Film and Broadcasting (USCCB-OFB) officially condemned the film as being unsuitable for a wide audience. But reviews produced privately for the office by priests and lay Catholics, and correspondence between the Vatican and the USCCB-OFB, show that the church at least notionally interpreted it as a positive response to the power of faith. Warner Bros. Studios, however, were keen to promote stories of religious outrage to boost sales and news coverage – a marketing strategy that actively contradicted Friedkin’s respectful and collaborative approach to working with both religious communities and medical professionals. Reports of Catholic outrage were a means of promoting The Exorcist rather than an accurate reflection of the Catholic Church’s nuanced response to the film and its scientific and religious content.

America magazine ran a special issue on the movie six weeks after its release. James T. Keane looked back at that issue:

Six weeks after the movie’s release, America devoted a special issue to the movie, titled “How to View ‘The Exorcist’,” including an editorial and four different commentaries on the film by former America editor Richard Blake, S.J., the Rev. Robert Lauder (who is still writing for America five decades later), Robert Boyle, S.J., and America’s redoubtable film critic Moira Walsh.

Father Blake didn’t mince words. “To begin at the beginning, The Exorcist is a $10-million failure. Like one of those outrageously expensive illustrated Bibles, it cheapens even the potentially redeeming elements of its message,” he wrote. “It is not obscene in the usual sense of the term, it is not religious and, finally, it is just not very good.” (He repented 26 years later in America, when “The Exorcist” was re-released.)

Father Lauder complimented the film as an impressive example of the horror genre, but he found it a “lesser work of art” in its exploration of religious themes, in part due to Friedkin’s directorial choices. “As a religious film,” he wrote, “The Exorcist is shouting when it should be whispering.”

Moira Walsh called the movie “wildly over-discussed” but also had no patience for critics who panned the movie simply because it dealt with religious topics. “I am also pretty much convinced that when a critic vociferously dislikes a film—for impeccably objective, aesthetic reasons, of course—he is really motivated by some sort of selective moral indignation,” she wrote.

This New York Times piece from January 1974 explores some of the extreme responses to the movie in the culture - a rise in calls to Catholic priests for help, fear over possible possession and so on. Just in the month after its release!

Priest-psychologist Eugene Kennedy is quoted in the piece, and is reaction was not unique among those anxious to remind the world that The Exorcist does not, in any way, represent the way Catholic Are Now:

Others, however, contend that the message of the film is fundamentally immature. “The bat tle of good and evil is not fought out on the level of demonology,” said Father Kennedy. “It is much more banal, like in the relations of a husband and wife. Being a Christian and a mature person means coming to terms with our own capacity for evil, not projecting it on an outside force that possesses us.”

Father Kennedy also criticized the film for suggesting that the solution to evil lies in outside help. “It ascribes mysterious and mystical power to the priest,” he said. “It's a kind of ‘Going My Way’ of the nineteen‐seventies.”

Father Woods said that a high percentage of his calls came from persons who were raised as Catholics but no longer practiced their religion. “It stirs up memories of all those descriptions of hell that you got from nuns,” he said.

Father Woods added that this was regrettable because, since the Second Vatican Council of 1962 to 1965, the church had adopted a more positive tone.

“It reflects the view that you are doing people a spiritual favor if you scare the hell out of them,” he said. “This was the way the church was when Blatty was a senior at Georgetown. But it's not the way the church is today.”

A priest in Commonweal reacted to the novel in 1972:

His line of reasoning in favor of diabolical possession is almost preEnlightenment: that bizarre phenomena which,for us, have no known explanation, must have a "supernatural" explanation. It resembles the"God-of-the-gaps" proofs for the existence of God, that he must be, in some way, the Answer to any number of mysteries we do not understand-- rather than the Lord and Father revealed to us in the self-emptying love of Jesus.

Blatty's implication that those who choose not to believe in Satan (and Blatty's story) have fallen for his game plan of convincing us that he does not exist has the same logic as the argument during the Red scare of the 1950s that the first thing a real

Communist learns is to deny that he is a Communist. Besides, if Blatty's devil really wanted to lay low the last thing he should do is take over the daughter of a beautiful movie star making a film on location surrounded by Georgetown Jesuits.

Of course, there’s truth in that reminder - to not let the sensationalism and Regan’s lack of agency as a victim blind us to the way that sin takes hold in our lives: through our misuse of our wills to turn from God and reject His love.

Of course.

An interesting moment, nonetheless, as you can almost feel the distress of some that this stuff that we are leaving behind is so stupidly popular, that this way of thinking about evil and sin that we know was just the attempts of an immature people to express what they didn’t understand and what sciences of all kinds now explain - is striking a chord?

Blatty responded to all of this in the pages of America:

Your issue on The Exorcist was fine. Fr. Robert Boyle’s insight into the fact that both novel and film derive much of their “harrowing impact from the refusal to analyze openly” is almost astounding in its penetration to the author’s intent. Fr. Robert Lauder makes impeccable distinctions. And Moira Walsh, alas, is discerning when noting that critics of the film base their judgements on “mutually contradictory” reasons. Dominican Richard Woods, for example, attacked the film in Time because “The devil’s true work is temptation…. That is almost entirely missing from the movie. The devil in the movie was an easy devil to handle.” And the following week, Fr. Woods’ colleague at Loyola of Chicago—Maryknoll psychologist Eugene Kennedy—put down the film because “the battle between good and evil is not fought out on the level of demonology. Being a Christian...means coming to terms with our own capacity for evil, not projecting it on an outside force that possesses us.” Or tempts us, I presume.

Such contradictions, when taken alone, are a source of bemusement and of wonder. But I am truly dismayed at the misconceptions held, not only by critics, but also defenders of the novel and film. And when I see that they are Jesuits, whom I thanked on the acknowledgement page of my novel for “teaching me to think,” I can only conclude that the fault must be mine, and that what I thought obvious, was not. The “fierce” opposition of America’s editor to explanations by “interested parties” has been duly noted; but perhaps his recognition of the “mystery of goodness” theme in the work has tamed him some. Perhaps just a bit. We do not ask miracles (not today). But may I clear up one or two of the misconceptions and make an occasional mild riposte?

….

3. Inasmuch as America’s editor commends Fr. Richard Woods for his views on possession as set forth in Catholic Mind, I return for a moment to the alleged “failure” of The Exorcist to come to grips with evil, and to the “devil as tempter” point of view. Quite aside from the fact that I believe the latter to be naive, mistaken and an excuse for evasion of confrontation with personal guilt; quite aside from the fact that I did not wish to examine this particular theme any more than I wished to examine the particular theme of Biafra in this work, instead preferring to focus on the neglected and far more positive, consoling and even joyous “mystery of goodness”; the fact of the matter is that the film deals precisely with Satan’s most potent attack on the race: the inducement of despair. It is aimed at those around the little girl, the observers of the possession, and particularly Fr. Karras, who is far more vulnerable to the attack. For Fr. Karras has rejected his own humanity: the animal side of his nature; the side that rends foods and chews and excretes; the side that kills over lust for a woman. The physical and seemingly spiritual degradation of the girl when possessed is aimed precisely at this vulnerability, stronger in Fr. Karras, but lurking in all of us (at least in the state of potency), and especially in those who, like Fr. Karras, have not lost but rather misplaced their faith because they have felt, “If there were a God, He could never love me”—or love a Regan MacNeil in the state of possession. From there to disbelief in God altogether is an easy and almost unconscious connection, but one that, at the last, Fr. Karras rejects along with despair. Thus, Fr. Blake, in my view, is mistaken when he observes that Fr. Karras “neither deepens nor loses his faith.” And when he complains that at the end of the film Chris MacNeil doesn’t seem to accept the faith as a consequence of witnessing the possession, he is looking for Disneyland, not life: for Bedknobs and Broomsticks instead of reality. When Jesus cured the blind and raised the dead, there were many who saw and yet did not believe. Faith has more to do with love than with levitating beds. And this aside, would a fictional depiction of Chris’s conversion cause a movie audience—or anyone in it—to convert?

Extended show notes. Great stuff!