"It would be a severe loss..."

Well, as of this writing, we are at almost 300 subscribers, so thank you all for joining up!

I’ll be posting a comment-open post next Friday (11/18), but am sending out this post just to touch base.

Reminder of the guidelines for this site. And yes, this will always be a free site. If you have any interest in supporting me, just buy a book or two.

Spoiler alert: the theme of next week’s post will be music.

Thanks to Rod Dreher for linking to the Jesus Livingston Seagull post on my blog, although I would take issue with him characterizing that tiny bit of (ancient) history as “stunning,” as he did on the Bird App. It’s not inherently “stunning” nor is it “stunning” in context. If you were there, this - or something like it - might have been your normal life. Not stunning at all.

Anyway, for the sake of further context-setting, here’s a reprint of one of a blog post from last year. The original is here.

As I’ve mentioned before, I have a small collection of popular and scholarly works about liturgy published around the time of the Second Vatican Council. I’m far more interested in trying to assess what actually motivated decisions than what ideologues and agenda-mappers sixty years later maintain.

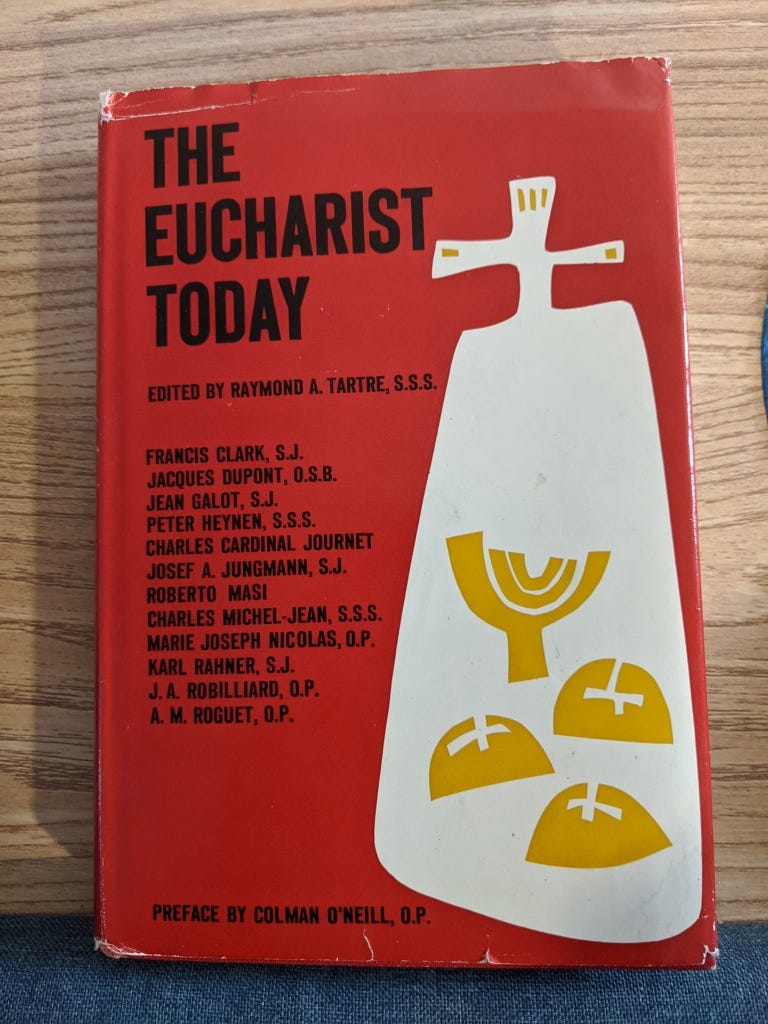

So, a few weeks back, I was perusing a few of these books as I worked out my thoughts on the whole worthy-to-receive debate (this post, for example. And this one.) I was leafing through The Eucharist Today, an essay collection published in 1967.

One of the most interesting aspects of reading discussions from this period is encountering the thread of caution. The scholars are all for reform, but except for the most enthusiastically ideological and iconoclastic, they have an historical awareness that prompts them to correct overreaching in advance.

So, for example, an essay by one A.M. Roguet, a Dominican.

One of the big issues of the period, as church functionaries and scholars did their reconstructive work, was to shape liturgical life so that everyone (they hoped) understood the centrality of the Eucharist (you know…source and summit) and understood it as a focus in which they should participate (you know…actively).

So for the sake of that cause, it was generally seen as absolutely necessary to diminish the importance of popular devotions – that had, it was believed, evolved as a compensation for the laity feeling distanced from the Eucharist. It was also seen as important to challenge Eucharistic adoration in all of its forms – processions, Benediction, 40 Hours’ Devotion – so that the laity would focus their spiritual attention on the Mass in an engaged, participatory kind of way, rather than as worshippers. The distinction was between active and passive, the assumption being that an emphasis on worship of the Blessed Sacrament = passivity.

If you want a sense of how this manifests itself in more recent times, consider the insistence on the part of liturgists that, for example, congregations stand during the reception of Communion, keep singing, and that there be no silence at all, discouraging kneeling and private prayer after Communion because, you know the Mass is public worship, a time to emphasize community, and not a time for private prayer, so get up off your knees, stand up, and sing louder.

These concerns occupy many of the contributions to this collection (published in 1967, remember) Roguet reflects much of the debate of his time, but expresses…that caution.

It is true that previous generations have to some extent made too much of processions and benedictions of the Blessed Sacrament…..But on the other hand, this suppression has gone too far. We do not have to apologize for this manifestation of Eucharistic piety under the lame pretext, for example, that it was unknown to antiquity….adoration is not therefore to be dismissed as superfluous simply because we possess Christ under presences other than that of the Eucharist….Liturgical piety would not be truly Christian if it were to mean the disappearance of every form of piety — Eucharistic, sacramental, contemplative, laudative — which, far from being foreign to the Mass, provide it with its framework, its subsoil, its atmosphere. (129-132)

All that is a preface to Karl Rahner’s contribution. Now, Rahner is a far more complex figure than many of his current supporters or detractors maintain. His caution here, mostly about the use of the past in shaping the present, is well worth reading and remembering:

‘What needs to be stressed is that the fact that there have been periods in which there was no actual eucharistic devotion outside the sacrifice of the Mass cannot be a valid argument against such devotions being genuinely Christian. It would be a severe loss to Catholic devotional life if a false romanticism about the early Church led to the abandonment of what has developed in the course of the history of devotion. Christianity is history. A practice with a thousand years of history behind it has its rights, even if they are not the first thousand years. Those who exalt the early centuries into an absolute standard in matters of devotion ought to do it consistently (or abandon it, as an absolute, altogether) ; which would mean applying it to fasting, to a thoroughgoing preference and pre-eminence for the virginal state over marriage, to the length of the Liturgy, to out-and-out monastic asceticism, and to many other things. It is only the mind of the whole Church of all ages that can pronounce on what is genuinely Christian, and humble reflection on the ultimate basic structures of Christianity, which are displayed in the Church in all periods but which do lead historically, both in theory and in practice, to conclusions which have not always been explicit and which yet, once given, become from then on part of the permanent self-fulfillment of the Church.’

As I have said before, the “comeback” of devotions such as Adoration and even the rosary, especially among young people, would have been unimaginable to those re-forming the Church’s life in the decade and a half after the Council. It is important to understand this as the context for the uncomprehending hostility that is often seen from those formed for ministry during that period. All of those practices were understood as essentially obstacles to a flourishing faith in the modern world. Rahner, here, is prescient as he points out the dangers - and illogic - of that approach.